Summary

Creatine Monohydrate

What is Creatine monohydrate?

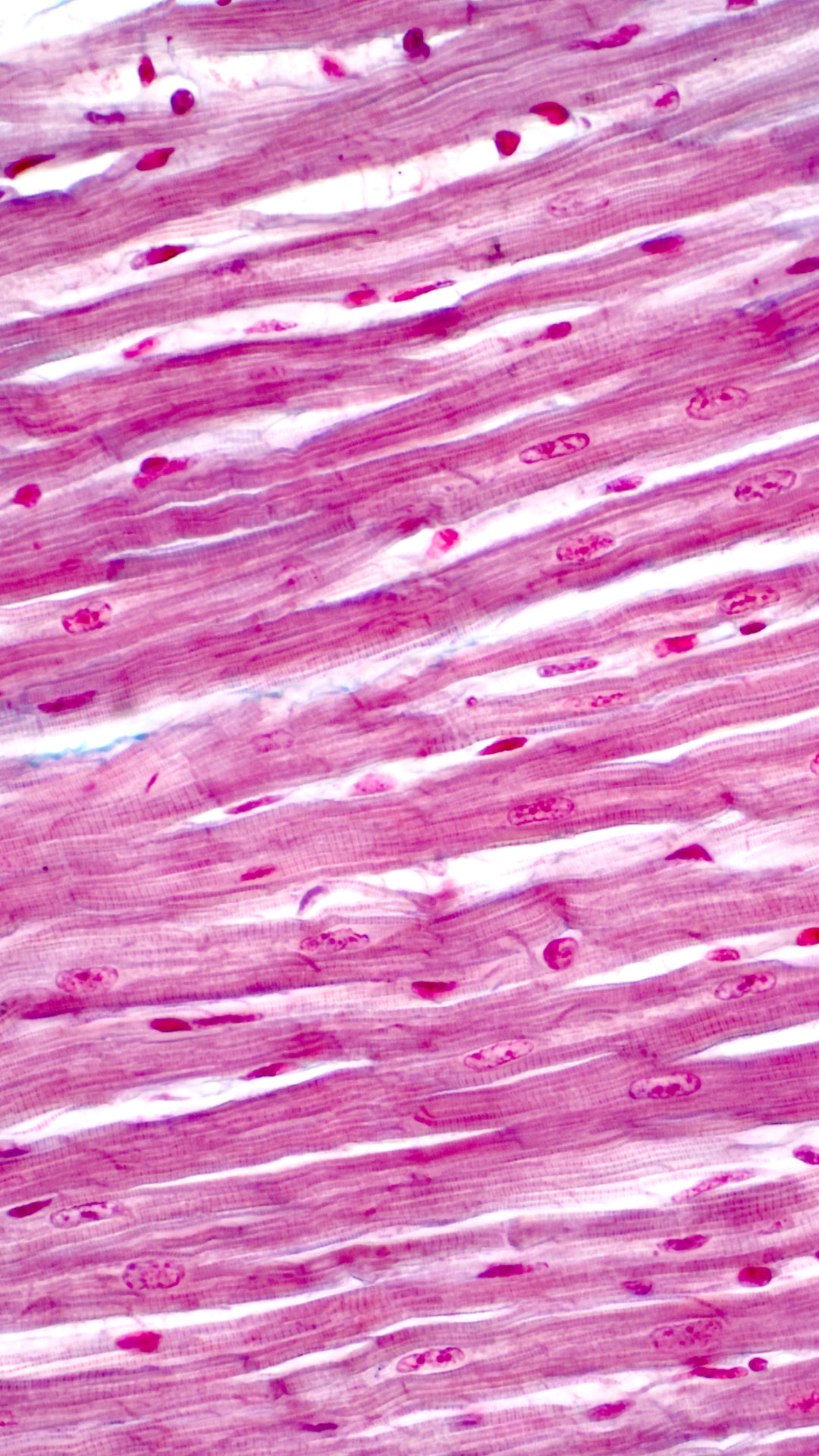

Creatine is a nitrogenous organic acid produced by your body, primarily in the liver and kidneys, from reactions involving the amino acids arginine, glycine, and methionine. Muscles contain about 95% of the creatine in your body, with the rest in other energy-hungry tissues such as the heart, brain, liver, kidneys, and reproductive organs.

Creatine can be phosphorylated to phosphocreatine in a reversible reaction sped by creatine kinase enzymes, and both creatine and phosphocreatine are key to optimal functioning of tissues with high, rapidly changing energy demands. Specifically, both are involved in a system that helps maintain (“buffer”) levels of ATP, the main energy currency of cells. In addition, creatine kinases use hydrogen ions, helping to buffer local pH. These enzymes also help deliver phosphocreatine to sites of need. While creatine serves many biological roles, its roles in providing energy at times of heightened demands underlie many of its benefits.

Our bodies produce roughly 1 to 3 g of creatine per day, but we consume creatine in food too. Animal foods such as fish and meat tend to be the richest creatine sources, so omnivore creatine intakes are typically higher than those of vegans.

Effects of creatine on lifespan and healthspan

While there’s been surprisingly little research on this subject, creatine does seem to extend the healthspan of some animals. For example, when fed a 1% creatine diet beginning at age 12 months (middle age, for these animals), creatine prolonged average (median) disease-free lifespan of female mice (C57BL/6J) by 9%.

Creatine targets several of the hallmarks that drive aging. For example, the aforementioned study documented that the creatine-treated animals had lower brain levels of lipofuscin, a dysfunctional pigment that accrues in lysosomes in cells. Lipofuscin is a kind of cellular waste containing lipids and misfolded proteins crosslinked together by metals such as iron, and lipofuscin accumulates in particular in non-dividing cells, including nerves and heart muscle cells. Lipofuscin clearly contributes to several age-related diseases, such as macular degeneration. Lipofuscin accumulation can be driven by several hallmarks of aging, including loss of proteostasis and disabled macroautophagy. In turn, lipofuscin accumulation can be self-perpetuating and exacerbate these hallmarks of aging, plus others.

Creatine also helps offset a few other hallmarks of aging, most notably mitochondrial dysfunction. By boosting cellular phosphocreatine, creatine helps maintain cellular ATP levels, stepping in for mitochondria when mitochondria cannot produce ATP at a sufficient rate. In addition, creatine helps shuttle inorganic phosphate from the mitochondria to sites of need in the cytosol. As a result, creatine is likely especially important when mitochondrial function is compromised, as during loss of blood flow, injury, and age-related mitochondrial dysfunction.

We think that creatine is likely to be especially important to human healthspan and lifespan owing to creatine’s ability to support the mass and strength of the musculoskeletal system. In the context of human aging, this is a BIG deal. Sarcopenia is the progressive loss of muscle mass and function with age, afflicting about 10% of people aged 60 and older, depending on how it’s defined. People with sarcopenia are prone to a vicious cycle of frailty: Loss of muscle strength and power makes falls more likely, and the increasingly brittle bones of older people make bones prone to fractures. The fractures then cause these people to unload their injured musculoskeletal systems, speeding muscle and bone loss, resulting in frailty that can ultimately be devastating — in the first few months after a hip fracture, there’s a three- to five-fold increased risk of dying from any cause, and average life expectancy after hip fracture is particularly severely truncated in the oldest adults.

This highlights a neglected point: The drivers of morbidity and mortality differ between species. Unlike mice, fruit flies, or roundworms, when humans fall, they fall hard, so maintaining musculoskeletal function during aging might be especially important for us big bipeds. The fact that most other supplements and drugs intended to counter aging don’t address this is one of their glaring limitations.

Positive effects of creatine on human health

Creatine might be the single most-studied performance-enhancing nutraceutical available. However, it’s now clear that creatine’s positive effects extend beyond what it was initially used for. Here are some of creatine’s main benefits.

Creatine improves muscle function

Supplementation consistently improves maximal strength, the ability to produce force quickly (power), and repeated sprint performance. In general, supplementation is most performance enhancing in activities requiring brief, maximal efforts with rest periods insufficient to allow complete recovery, as typifies many team sports and recreational activities such as lifting weights. The effects of creatine supplementation on muscle ATP levels contribute to these positive effects. Creatine can also boost muscle carbohydrate (glycogen) stores, which strongly affect performance in most high-intensity exercise.

Creatine increases skeletal muscle mass

When creatine is taken alongside appropriate exercise training, people also gain muscle faster in both the lower and the upper body. Notably, creatine’s positive effects on muscle mass and performance occur in older adults too. Exactly how creatine helps build muscle and boost adaptations to exercise isn’t clear, but there are certainly several mechanisms at play. Several of these relate to aiding recovery from exercise. For example, in the short term, creatine reduces exercise-induced muscle damage and soreness. Creatine probably also increases the synthesis of new contractile proteins in skeletal muscle via numerous actions, including by increasing the hydration of muscle cells, affecting a muscle stem cell niche (satellite cells), and stimulating growth-promoting nutrient sensing pathways, such as IGF-1 and mTOR. To the uninitiated, the latter might seem counterproductive in the context of aging as systemic increases in IGF-1 and mTOR are in some cases thought to contribute to aging. However, we’re specifically talking about skeletal muscle here, a tissue that we want plenty of anabolic activity in if we want to stay strong as we age. In this way, creatine is arguably positively affecting another hallmark of aging (dysregulated nutrient sensing), in a tissue-specific way.

Creatine supports bone health

There is preliminary evidence that creatine supplementation amplifies the positive effects of resistance exercise on bone health. For example, in a study of older men, only those taking creatine increased their bone mineral density. While it’s been speculated that creatine use directly affects bone building cells and bone breakdown, it might simply be that creatine is good for bone because its use permits greater exercise loads. Since bigger, stronger muscles pull harder on bones, bones must adapt to withstand these higher forces.

Creatine can enhance cognition and motor skills

In recent years many of us have become increasingly interested in creatine’s roles in brain health. The brain is a famously energy-hungry organ, accounting for about 20% of whole-body oxygen consumption despite amassing only about 2% of bodyweight, and the phosphocreatine system is involved in brain energy homeostasis. (Tangentially, some people even consider creatine to be a neurotransmitter, for creatine is released from some neurons when they fire and is then taken back up via the creatine transporter.) The brain’s energy demands fluctuate substantially over time, and brain energy status can be compromised by a range of stressors, including extended wakefulness, hypoxia, and injury. As in skeletal muscle, creatine supplementation can boost tissue creatine stores in the brain, albeit to a lesser extent than skeletal muscle.

By boosting brain energy status, creatine can improve brain function, even in healthy people. Creatine really comes into its own when the brain has to work hard. Several studies have reported that relatively high doses of creatine can help maintain various cognitive and motor functions when people are short on sleep, for example in tests of memory, language, and numeracy. Creatine might also help maintain physical performance during sleep loss, as documented in a study of rugby players that assessed their passing accuracy, a sport-specific motor skill. Regarding other stressful brain states, creatine supplementation can support cognitive functions, such as attention, when brain oxygen delivery is compromised by hypoxia.

While this subject is infancy, creatine seems to hold promise in the context of some neurodegenerative conditions and forms of brain trauma too. Despite billions of dollars being pumped into their study, we still lack effective treatments for some neurodegenerative conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease. A promising recent pilot trial found that giving Alzheimer’s patients a big dose (20 g per day) of creatine for 8 weeks increased brain creatine stores and sharpened brain function in several cognitive tests. Regarding brain injuries, a study of children and adolescents with traumatic brain injuries reported remarkable improvements in behavior and cognition following high-dose creatine use. These reports are encouraging but need replicating.

Creatine can lift mood

There are likely several common brain disorders in which creatine will prove a helpful adjunct treatment. One of the more common and burdensome of these is major depression. Some antidepressant medications take several weeks or months to produce meaningful responses, and there is evidence that a dose of creatine roughly equal to that in Coastline can accelerate treatment responses when used in conjunction with antidepressants. In keeping with this, surveys of creatine intakes in the general population have highlighted a possible protective role of creatine against depression. For instance, compared to US adults in the lowest quarter of estimated creatine intakes, adults in the highest quarter of estimated intakes had 32% lower odds of having depression.

Creatine might help counter long COVID (post-COVID conditions)

Creatine appears to be a great option for people with long COVID symptoms, countering many symptoms at a dose similar to the one in Coastline. Once again, some of this seems to relate to creatine’s ability to support the energetic status of relevant tissues, such as the brain.

Creatine might aid cardiovascular health

Through reactions involving the donation of methyl groups, creatine intake influences levels of an amino acid named homocysteine, which might be an independent risk factor for cardiovascular problems. Specifically, the process of synthesising creatine in the body requires S-adenosylmethionine, a methyl donor. The result is an increase in homocysteine. Creatine supplementation reduces the body’s need to make its own creatine, diminishing S-adenosylmethionine consumption and homocysteine formation.

Our use of creatine

Regarding dose, as little as 2.2 g creatine per day can improve memory in some people, and systematic reviews have shown that, almost irrespective of dose, creatine can improve muscle strength in both the lower and upper body, although older adults might benefit from creatine loading and/or slightly higher doses than those that work well in younger people. The creatine dose in Coastline was influenced by this finding, plus that of a study that found that a moderate dose of creatine improved how the bones of older men responded to a resistance training programme.

Regarding timing, creatine is in the morning step of Coastline for several reasons. One is that this step is intended to be taken with food, and the addition of carbohydrate and/or protein have been shown to increase the retention of creatine in tissues. Another reason is that a single dose of creatine can acutely improve some cognitive functions, perhaps especially when the energy status of the brain is challenged, as against a background of insufficient sleep.

Regarding form, almost all of the research on creatine uses regular creatine monohydrate, a white, relatively water-soluble, bland-tasting, almost perfectly bioavailable substance. This is what we use too. You might have come across micronized forms of creatine such as Creapure®. Other than a practically meaningless effect on solubility in water, micronization has no inherent advantage over other monohydrate products with larger particle sizes — to your body, creatine monohydrate is creatine monohydrate.

Creatine typical dietary intakes and safety

Creatine is present in animal foods, and most of us consume 1 to 3 g of creatine each day from foods. Of concern, however, a study of US adults aged 65 and older found that 70% had estimated creatine intakes below 1 g per day, and 20% had estimated daily intakes of 0 g. So, many of us could do with quite a lot more creatine.

Omnivores have higher creatine intakes than people on vegetarian or vegan diets, and small fish are among the richest sources of creatine, with herring containing about 11 g per kg. There is evidence that in some ways people who don’t eat meat or fish benefit more from creatine supplementation than those who do.

Regarding safety, long-term creatine supplementation is very safe – even at doses of up to 30 g per day for 5 years! One thing to note is that taking creatine is bound to slightly increase your levels of creatinine, a marker often included in blood tests as a proxy of kidney function. This is because about 1 to 2% of intramuscular creatine is degraded into creatinine, which is then excreted in the urine. For this reason, people with massive muscles and people who do high levels of activity that acutely produces exercise-induced muscle damage tend to have higher creatinine levels. This is normal physiology and is nothing to worry about, and another marker named cystatin C tends to better reflect kidney function than creatinine.

Order Your Coastline Welcome Pack Today

13 foundational ingredients. 1 simple system. $165 value for only $120 including FREE glass shaker.